Lallemand’s new NovaLager dry lager yeast

Lallemand have recently released a new strain of true bottom-fermenting lager yeast in dried format dubbed ‘NovaLager’ which exceptional performance and clean flavour without the usual sensitivities and downsides of the traditional lager yeast strains available to the domestic market, such as slow fermentation, temperature sensitivity, high pitch rate requirements and ‘off flavour’ production – such as diacetyl, acetaldehyde and sulphur. NovaLager promises minimal off-flavours, a subtle ester profile and a wide temperature range. Attenuation is high, flocculation is medium and phenolics low – akin to many traditional strains. Lallemand report being able to complete a fermentation in as little as 6 days, which is common for many ale strains, but very quick compared to a traditional lager fermentation timeline. The acceptable temperature range for NovaLager is stated to be 10 – 20°C (50 – 68°F), meaning successful fermentations without dedicated temperature control a possibility (though not recommended, as with any yeast).

You can purchase NovaLager in Australia from this link: HERE

Taken from Lallemand’s website:

“LalBrew NovaLager™ is a true bottom-fermenting Saccharomyces pastorianus hybrid from the novel Group III lineage that has been selected to produce clean lager beers with distinct flavour characteristics and superior fermentation performance. LalBrew NovaLager™ is a robust lager strain with ideal characteristics for lager beer production including fast fermentations, high attenuation. The distinct flavor profile is very clean, slight esters over a wide temperature range. This product is the result of the research and development work of Renaissance Bioscience Corp. (Vancouver BC, Canada) in partnership with Lallemand Brewing. LalBrew NovaLager™ was selected using classical and non-GMO breeding methods to obtain a novel Saccharomyces cerevisiae x Saccharomyces eubayanus hybrid strain that defines a novel Group III (Renaissance) lager lineage that is distinct from any other traditional Saccharomyces pastorianus strains. This strain is a low VDK/diacetyl producer and utilizes patented technology from the University of California Davis (USA) that inhibits the production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) off-flavors, therefore reducing the maturation time associated with lager beer production.”

Speaking as to the specific yeast properties, Lallemand provide the following details:

Percent solids 93% – 97%

Viability ≥ 5 x 109 CFU per gram of dry yeast

Wild Yeast < 1 per 106 yeast cells

Diastaticus Negative

Bacteria < 1 per 106 yeast cells

While Lallemand traditionally do not provide specific attenuation figures for their strains - preferring instead ‘low’, ‘medium’ and ‘high’, brewing software profiles have NovaLager’s attenuation listed as 84%, a number which I have found to be accurate in my testing (discussed below).

NovaLager joins Lallemand’s collection of other recently released hybrid/engineered/newly discovered yeast strains, such as Philly Sour (a lactic acid-producing wild yeast with low contamination risk), Farmhouse (non-diastatic hybrid ale yeast, capable of producing very dry saisons with the expected phenolic flavours, in as little as 5 days, without the risk of over-attenuation common with traditional strains).

Anyway – with the technical stuff out the way, how does the yeast perform in a real-life homebrew scenario? Glad you asked – I’ve been testing it in a semi-technical way!

BJCP Style Guide5D. German PilsAroma Medium-low to low grainy-sweet-rich malt character (often with a light honey and slightly toasted cracker quality) and distinctive flowery, spicy, or herbal hops. Clean fermentation profile. May optionally have a very light sulfury note that comes from water as much as yeast. The hops are moderately-low to moderately-high, but should not totally dominate the malt presence. One-dimensional examples are inferior to the more complex qualities when all ingredients are sensed. May have a very low background note of DMS. Flavour Medium to high hop bitterness dominates the palate and lingers into the aftertaste. Moderate to moderately-low grainy-sweet malt character supports the hop bitterness. Low to high floral, spicy, or herbal hop flavor. Clean fermentation profile. Dry to medium-dry, crisp, well-attenuated finish with a bitter aftertaste and light malt flavour. Examples made with water with higher sulfate levels often will have a low sulphury flavor that accentuates the dryness and lengthens the finish; this is acceptable but not mandatory. Some versions have a soft finish with more of a malt flavor, but still with noticeable hop bitterness and flavor, with the balance still towards bitterness. Mouthfeel Medium-light body. Medium to high carbonation.

Source: https://www.bjcp.org/style/2015/5/5D/german-pils/ |

THE TESTS

|Experiment 1: Pilsner

First cab off the rank, a batch of simple pilsner. I style that leaves very little in the way of malt, hops and water chemistry for yeast flavours to hide behind. Fermentation control and yeast selection is crucial in order to get a clean, crisp result with little yeast character. A very easy style to get very wrong.

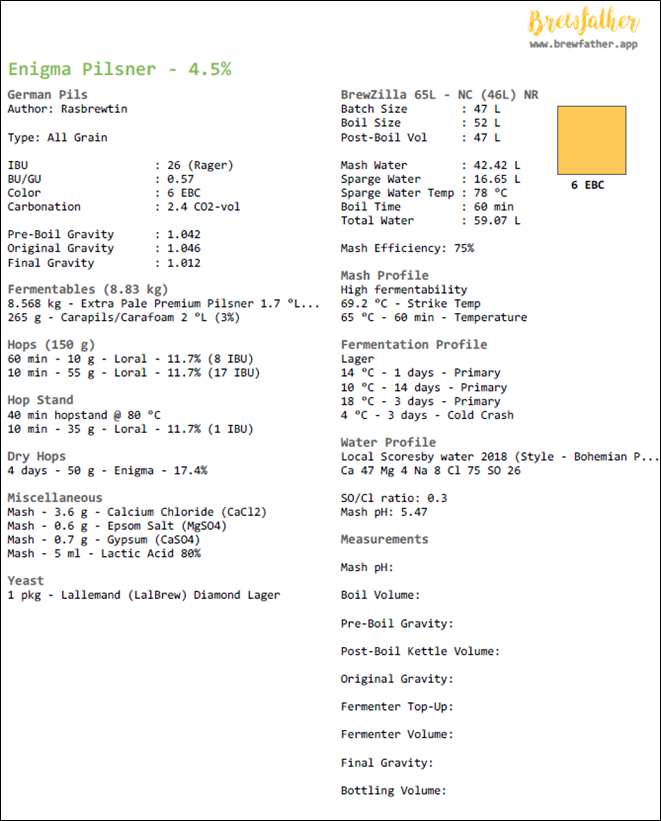

I used my go-to pilsner recipe (available HERE and provided below). Basically, a light base malt with a dash of Carapils for head retention. Hop choice was somewhat unconventional, but still appropriate for the style: Loral: “it is described as a ‘super noble hop’ with its wonderful floral and herbal notes followed by a backdrop of citrus and earthy character. A touch of sweet fruity aroma rounds out this well-balanced hop.” On occasion, I dry hop this beer with Enigma hops to turn it into a delicious hoppy pilsner with a Pinot Gris like flavour and aroma, with hints of raspberries and redcurrant all the way through to rock melon and light tropical fruit.

At the time I was given a sample of the yeast for testing purposes from the good people at Kegland, I had coincidentally just brewed a double-batch of this beer which I had racked into HDPE no chill cubes and thrown in my pool, which chills the wort pretty quickly to lock in the IBU’s and a lot of the volatile aromas. Essentially, I had two batches of identical wort that I could ferment with two different strains of yeast.

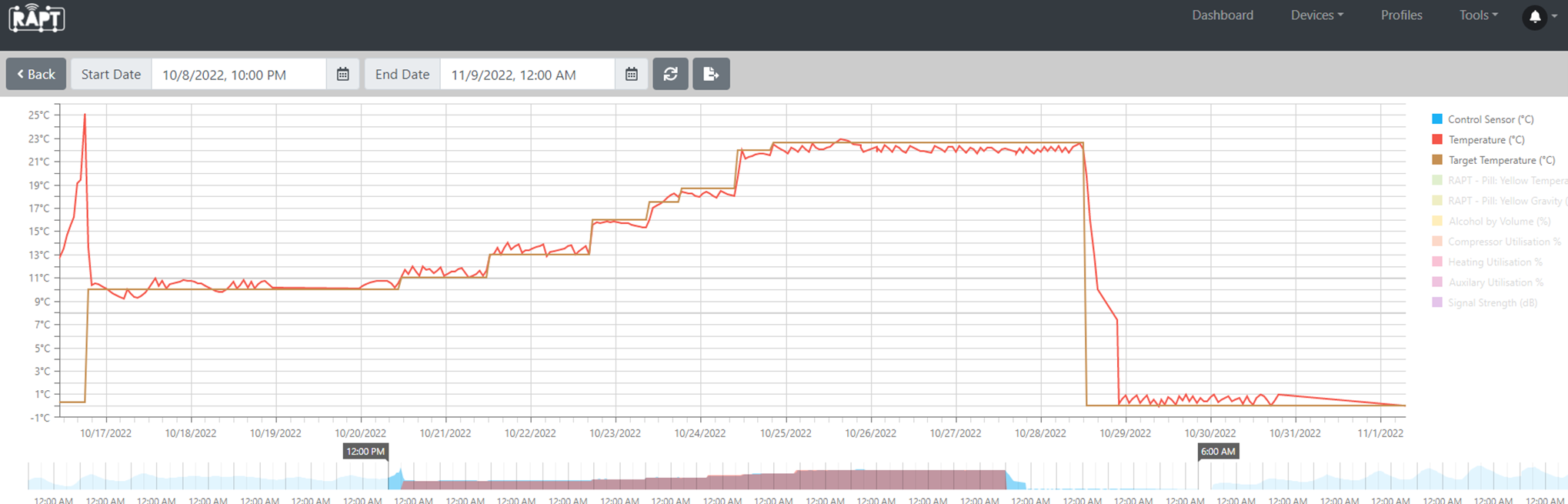

For the first batch (hereafter referred to as ‘the control batch’), I used Lallemand’s Diamond Lager and fermented as I usually would: I drained the HDPE drum into the Fermzilla Tri-Conical from a height to get plenty of aeration (side note – oxygenating with pure O2 isn’t particularly necessary with dry yeast). I used a healthy pitch rate on the higher end of the manufacture suggested range, cold start at ~10c (50f) to keep the esters under control, ramped the temperature gradually from day 4, as terminal gravity approached (usually for me when the krausen begins to subside), I made sure the temperature was at 23c (73f) to conduct a diacetyl/VDK rest. As with most traditional lager strains, D-rests are important steps to avoid your beer tasting like a butter-bomb. I also attached a spunding valve at this stage to catch the last gasses of fermentation so the beer would be mostly carbonated at the end (spunding so late in the fermentation would have had almost nil effect on ester suppression). Once the gravity was stable over three days, I crashed the temperature down to 0.5c(33f) to clear the beer and after 5 days, kegged the beer into a CO2-purged keg with 0.3g of sodium metabisulfite to further guard against oxidation. At this point, I adjusted the beer’s pH to 4.3 with phosphoric acid. For crispness and so that I could rule out pH as a variable between the two batches. From pitching the yeast to cold crashing, it was exactly 12 days followed by a 3 day cold crash. A copy of the fermentation temperature log is below.

For the second batch, I used the fresh 20g pack of NovaLager yeast given to me to sample. Again, I drained the HDPE drum of wort from a height to aerate it. I threw the fermenter into the RAPT Fermentation Chamber (yes, I’m sponsored by Kegland…) and set the temperature to 14c, which is the middle of the temperature range suggested by Lallemand. My thinking here is that this should give a good indicator of the yeast in ‘normal’ conditions. Most punters at home without fancy equipment could get away with 14c without temperature control in the Australian winter down here in Melbourne. If the yeast performed poorly at this temperature, I would consider it as not delivering on what it promised. I fermented the control batch at the bottom of its temperature range to get optimum cleanliness. This should be the best you can get out of this strain and put up a fierce fight against NovaLager.

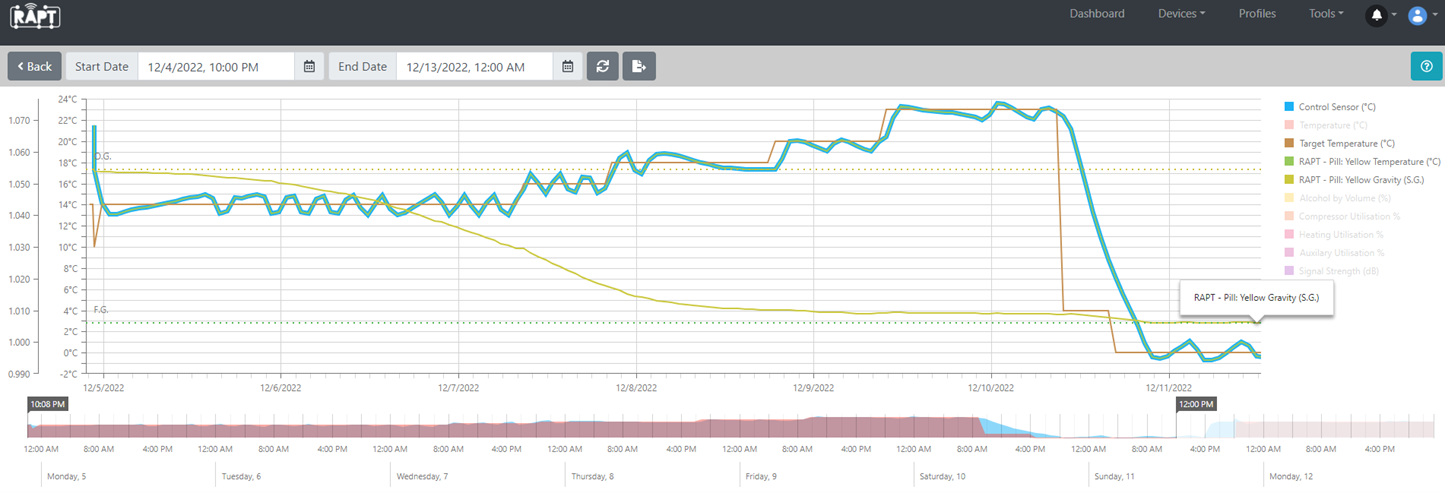

The ferment took a couple of days to kick off from the 14c starting point, but once it did, it powered towards terminal gravity. I gradually ramped the temperature as the beer got out of the ester danger zone with the aim to get to the D-rest temperature as terminal gravity approached, just to ensure the yeast were still active at this stage. After a couple of days at 23c for a D-rest, I cold crashed it to clear. The RAPT Pill and Rapt Fermentation Chamber allowed me to control and log the temperature through the RAPT Portal. The fermentation log is below (blue line = temperature; yellow line = gravity):

The results

Both beers tasted good straight into the keg, albeit that it was clear they would both do well with a bit of conditioning time in the keg as a bit of haze remained and the flavours were somewhat muddled/undefined (I guess you could say they needed time to ‘lager’, which loosely translates to ‘to store’.

Side note: ‘Lagering’ is not always necessary with excellent fermentation practices; I recall a podcast discussion with Dr Charlie Bamforth (watch this quick video) in which he summarised that very little biologically happens when beers are lagered as the temperature is simply too cold. Lagering is more so the residual solids in the beer flocculating out, taking with them the residual undesirable compounds, such as yeast cells, hop oils and polyphenols (tannins). Simply put, a well-made beer that is adequately fined/cleared would not need to be conditioned as one that is not. However, if the beer wasn’t crystal clear when it went into the keg, then lagering can definitely help, as was the case with my beers. … but I digress).

After just shy of a month in the keg, the control batch was a very good beer. True to style clarity, clean, crisp mouthfeel with a balanced body that gave the illusion of creaminess due to the solid carbonation. There was almost nil esters and a very subtle sulphur, which in small amounts is acceptable for style and surprisingly pleasant. The hop flavour was subdued but there was a supportive bitterness that can only be described as ‘balanced’. The flavour was delicately malty with dominant white bread and a very slight corn sweetness that finished crisp. I detected very little esters and nil diacetyl. The beer reminded me of a premium Italian pilsner (imagine Peroni Gran Riserva Puro Malto and Birra Moretti’s love child). Overall, a textbook pilsner in flavour.

The NovaLager batch after about a month in the keg was also very good. With time in the keg, the different flavours became more defined (I often find lagers to ‘reveal’ their flavour with time). It took slightly longer to clear than the control batch (see picture to the right).

Much like the control batch, the NovaLager beer was a very clean, crisp and refreshing beer. Perfect for the Australian summer I was experiencing. There was very little in the way of esters, at most some very slight red apple flavour. There was nil sulphur and nil diacetyl. To me, this beer tasted ‘less traditional’ than the control, potentially due to the total absence of sulphur, which can often lend to the beer’s crispness and lasting taste. A very good beer, just not traditional tasting. Imagine the household-name macro lagers of Australia and some USA beers: Victoria Bitter, Carlton Draught, sort of Budweiser, etc. Clinical cleanliness.

In summary, the two beers differed in terms of their ‘traditionalness’. Both were very clean, but the NovaLager was cleaner. Maybe too clean? You don’t realise just how much you appreciate the small amounts of sulphur and diacetyl until they’re gone – likely why they’re listed in the BJCP style guide above. The NovaLager beer was only guilty of lacking character.

I wouldn’t use NovaLager for a traditional style as with the extended conditioning or fining steps required to get it to taste ‘right’ negate the benefits you get from a fast-fermenting yeast: better to take a slower, traditional ferment with a traditional yeast if you want this. Treat the yeast right and you will have fully conditioned beer in as little as 3 weeks. Heck, you can even increase the temperature gradually as I did and have it grain-to-glass in 10 days if you fine it with gelatine, BioFine or PVPP.

This got me to thinking: where would I use this yeast then? NovaLager seems to be a perfect fit for the non-traditional lager styles out there that have increased in popularity in recent years. Examples include: cold IPA’s, hoppy lagers, New Zealand Pilsners and hazy lagers, just to name a few of the loosely defined styles. NovaLager would also suit many of the Australian craft breweries cheaper offerings, be they lager or ales, such as Mountain Goat’s Good Beer, Furphy, 150 Lashes and even Australian iconic lagers, such as Victoria Bitter (‘VB’), Carlton Draught, Carlton Dry (just add amylase enzyme). Really, any beer that has almost no discernible yeast flavour and hospital-grade cleanliness/crispness.

Further Test: German Schwarzbier (black lager)

The modern lager styles listed above are no-brainer good candidates for NovaLager, but I was still curious to see if it could produce a good example of a more traditional European style, albeit one where it’s lack of sulphur would not be a downfall.

Heading into autumn here in Melbourne, a German Schwarzbier (aka black lager) seemed a perfect candidate. A clean, crisp full-strength lager with a respectable level of maltiness, subtle coffee and roast flavours, and an almost-black colour. The malt usually masks most yeast flavours in these styles.

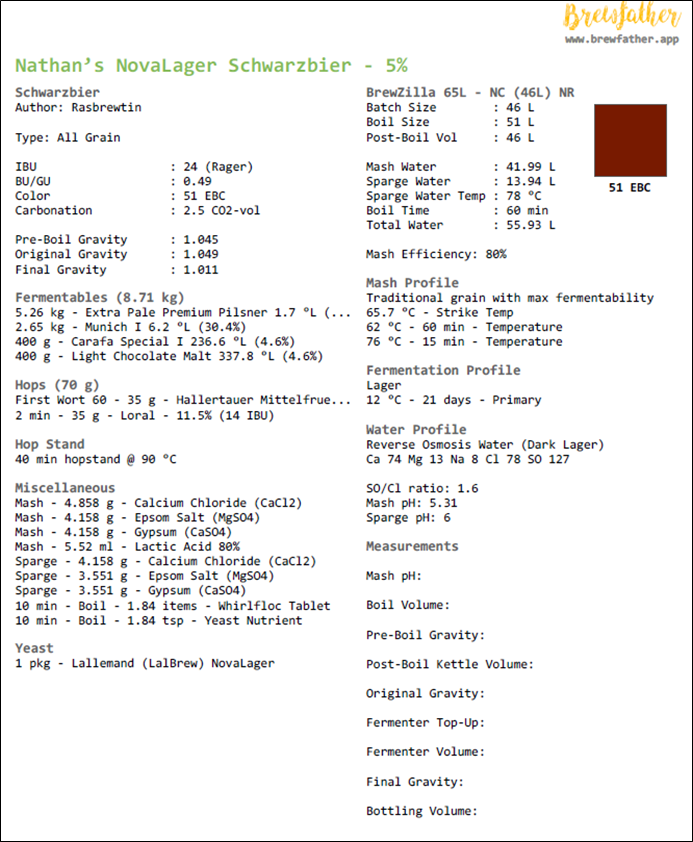

I devised a recipe (recipe here and provided below) aiming for the ‘middle of the road’ in terms of style guidelines (ABV, FG, IBU, EBC). Light pilsner makes up 60%, a wack of light Munich for malt flavour and Carafa 1 and light chocolate malt for colour and a subtle roast/chocolate flavour.

I brewed it on my 65L Brewzilla in my usual manner. I hit all of my targets, hot filled (no chilled) the wort into HDPE 23L cubes which I then threw into my pool to cool them fast.

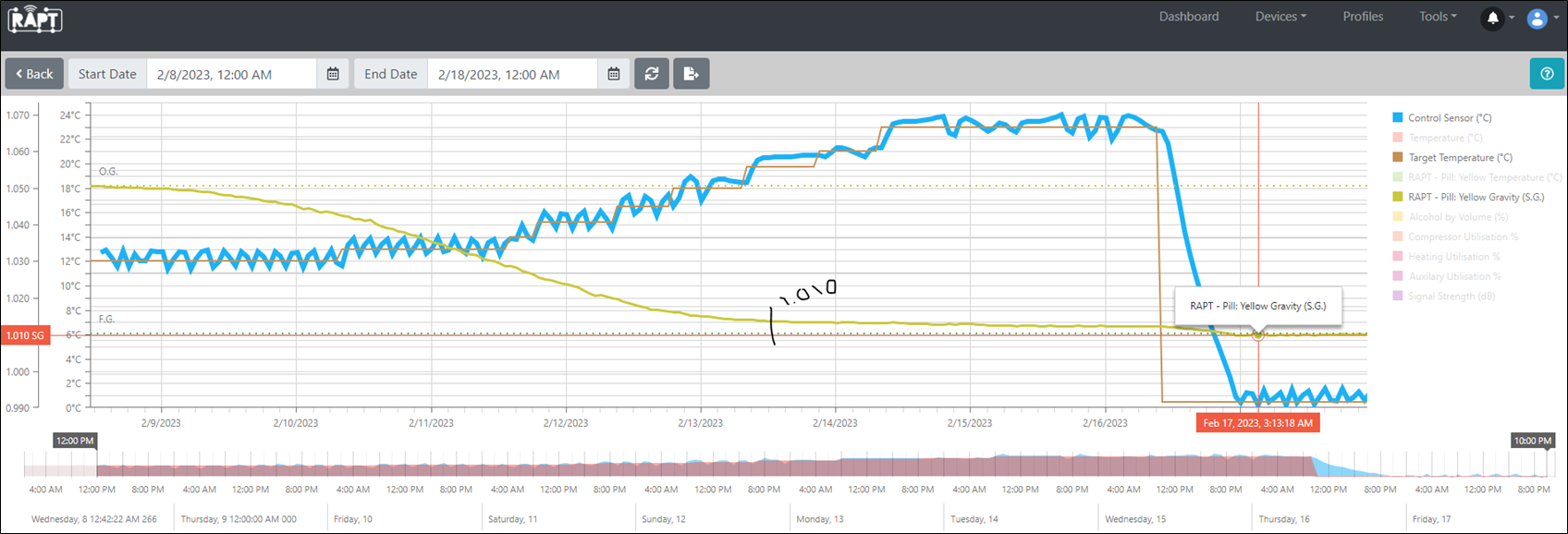

I measured out about 400ml of fresh slurry from my last batch of NovaLager pilsner and it was off and fermenting within a few hours (not uncommon with an big, active pitch of fresh yeast). I started the fermentation off at ~12c before following my usual lager temperature profile by slowly ramping up to my usual D-rest temperature as soon as the critical ester window of fermentation was over.

Fermentation slowed drastically by day 5 when it hit 1.013 after which point it bubbled for 2 more days chewing those last 3 gravity points off to settle at 1.010. I crash chilled it for three days before kegging (fermentation log pictured below). The sample taste of the beer at this point was surprisingly pretty good: clean and crisp with a nice balance between malt sweetness and hop bitterness. Still somewhat cloudy with chill haze, which is to be expected having only used whirlfloc thus far.

I adjusted the pH of this beer down to 4.3 with phosphoric acid and to try something a little difference, I added gelatine to flocculate/clear the beer in the hopes this would condition the beers flavour quicker, reducing the need for extended lagering. To do this, I added one teaspoon of gelatine granules to 100ml of 75c water before squirting it through the PRV hole on the keg lid whilst I was slowly running CO2 in through the in post.

After a few days in the keg, the beer was brilliantly clear (see photo to the right). The flavour profile of the beer had improved quite a bit since kegging, despite there being only three days difference. Goes to show how much the residual particulate in the beer can make a difference to the flavour. To my tastebuds, the ‘layers’ of flavour became more defined with it easier to separate the crispness, from the bitterness, from the malt sweetness. Hard to explain using words, but it’s kind of like that scene from Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory where Charlie tries the ‘three course dinner bubblegum’ and is able to pick out the individual foods with ease. The flavours could be separated on the palate easier than a very fresh beer.

Overall, this is a recipe I would turn to again next time I wanted to make a black lager.

Conclusion

The NovaLager experiments have been fun. It is not often yeast labs release lager strains that are much different than the existing options. Usually, the revolutionary developments are reserved for the niche ale strains, such as those used for hazy hop bombs or Belgians. I’ve always found this peculiar despite lager beer being the most produced style in the world.

NovaLager does what it says on the box in that it delivers clean lagers in a short timeframe without any of the pitfalls associated with traditional lager brewing. However, NovaLager is not the answer to every lager style and, in my view, would be better avoided for the very traditional styles where traditional lager yeast flavours are desirable, no matter how subtle they may be. Despite it usually being associated with a poor fermentation, sulphur plays an important part in traditional pale styles of lager, such as pilsner. I missed this in the pilsner I made with NovaLager.

NovaLager would make a great option for the new, modern styles of lager, such as cold IPA’s, NZ pilsners, hoppy lagers, macro light lagers and any other style where yeast flavour plays no part and you simply want to turn sugar to alcohol.

BrewFather Recipe Sheet - Enigma Pilsner

Nathan's NovaLager Schwarzbier